FAQ : What is the history of opal? Are opals bad luck? Is opal bad luck? Why and when did superstition begin to surround opal?

Opal… the Bad Luck Stone?

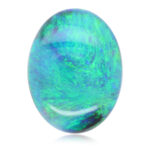

For many years, the opal has tried to shake off rumours and wives tales about the stone bringing bad luck. Perpetuated by folk lore, mistaken identity, superstitions, family tales and disgruntled diamond traders, the opal has had a pretty tough life. As we entered the age of reason and science, this belief has somewhat fallen by the wayside, but a glimmer of the superstition still survives today. Of course, like any unprovable theory, you’ll have to make up your own mind, but we’ve got our feet planted firmly in the non-believers camp. After all, we’ve owned and loved opals for over forty-five years and they’ve brought us nothing but good luck!

The Luck of the Opal: A History

The folklore connected with crystals, gems, and precious stones is as old as it is varied. Much of this tradition dates back to the beginnings of civilization, when jewelry was worn not only as adornment but also as protection against occult forces and human foolishness. Amethyst, for example, was thought to sober drunks, quell sexual passion, and cure baldness. Aquamarine was believed to protect seafarers, while emeralds increased fertility and intelligence, imparted prophetic ability, and other wild talents. Rubies provided defense against every kind of misfortune, made hostile neighbors friendly, and promoted one’s stature in the community.

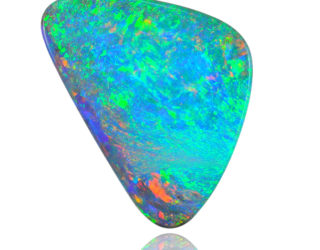

The opal’s nasty reputation however has troubled folklorists for centuries. Fantastic legends have grown up around this harmless stone, cautionary tales designed to discourage those who might otherwise find themselves mortally attracted by its fiery brilliance. To this day, the odd prejudice against opals remains alive and well in some corners of the world, especially in the backwaters of southern Europe and the Middle East, where jewellers won’t carry opals and customers won’t buy them.

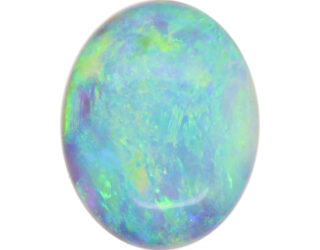

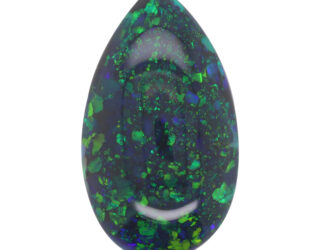

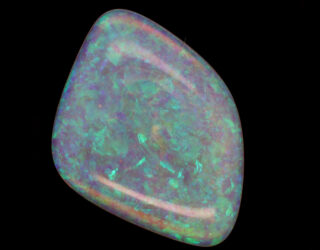

Throughout history, while many stones were prized for their positive magical qualities, others were denounced as vessels of evil. No gem was more vilified than the poor opal. Witches and sorcerers supposedly used black opals to increase their own magical powers or to focus them like laser beams on people they wanted to harm. Medieval Europeans dreaded the opal because of its resemblance to “the Evil Eye,” and its superficial likeness to the optical organs of cats, toads, snakes, and other common creatures with hellish affiliations.

An opal completely contaminated with evil were believed capable of maiming or even killing a person foolish enough to wear or own it. Tales alleging to prove this are few in number, but the belief persists nevertheless, like those old but curiously tenacious admonitions about walking under ladders, stepping on a crack in the sidewalk, or allowing a black cat to dart across one’s path. Popular superstitions such as these will be with us always, but however fanciful they may be, most have prosaic origins.

The early years – the “good luck” opal

The Romans established opal as a precious gemstone, obtaining their supplies from traders in the Middle East. Opals from this era are thought to have come from Cernowitz, a mountainous region in what was at that time Hungary , but now Slovakia. However early Romans believed the source was India, an incorrect belief promoted by traders in order to protect their interests.

They believed the opal was a combination of the beauty of all precious stones, and it is well documented in Roman history that Caesars gave their wives opal for good luck. They ranked opal second only to emeralds, and carried opal as a good luck charm or talisman because it was believed that like the rainbow, opal brought its owner good fortune. In the days when Rome spread her legions across Europe and Africa, a Roman Senator by the name of Nonius opted for exile rather than sell his valuable opal to Marc Antony who wanted to give it to his famous lover Cleopatra.

In fact, in Roman times, the gem was carried as a good luck charm of talisman, as it was believed that the gem, like the rainbow, brought its owner good fortune. To the Romans, it was considered to be a token of hope and purity. It was also referred to as the “Cupid Stone” because it suggested the clear complexion of the god of love. The early Greeks believed the opal bestowed powers of foresight and prophecy upon its owner, while in Arabian folklore, it is said that the stone fell from heaven in flashes of lightning. The Oriental traditions referred to them as “the anchor of hope”. Lucky opal – the stone of hope, the birthstone of October.

Special Powers

Early races credited opal with magical qualities and traditionally, opal was said to aid its wearer in seeing limitless possibilities. It was believed to clarify by amplifying and mirroring feelings, buried emotions and desires. It was also thought to lessen inhibitions and promote spontaneity.

In the 7th Century it was believed that opals possessed magical properties, and centuries later Shakespeare was attributed with the description of opal as “that miracle and queen of gems”. Eastern peoples also dealt very heavily in this precious stone, which was believed to bring luck and to enhance psychic abilities.

However, the entire time the Hungarian mines supplied Europe with opal, including a stone for the crown of a Roman Emperor, superstitions circulated attributing evil powers and maladies to the colourful stone. In the eleventh century, Bishop Marbode of Rennes wrote of opal, “…Yet ’tis the guardian of the thievish race; It gifts the bearer with acutest sight; But clouds all other eyes with thickest night.” This is thought to be based on the idea that opal granted its bearer with invisibility, therefore it was a talisman for thieves, spies and robbers!

Opals were also thought to have teleportation powers. A piece of opal jewelry might suddenly disappear from some obvious place, only to turn up weeks or months later somewhere unexpected. Of course, forgetfulness might also be to blame.

Fear and loathing of the opal did not discourage the development of a counter folklore which cast the stone as a symbol of hope, innocence, and purity. The Arabs of Mohammed’s time were quite enamored of the gem, and were convinced they were carried to earth on bolts of lightning. European writers and poets of the Middle Ages also sang the opal’s praises, claiming it had curative effect on bad eyes, protected children from predatory animals, banished evil, and made entertainments, friendships, and romances much more intense and enjoyable. Fair-haired girls in Germany and Scandinavia were encouraged to wear opal pins in their hair, as they were thought to add magical luster to their golden locks and protect them from freezing rain, wind, and other vicissitudes of the Nordic climate.

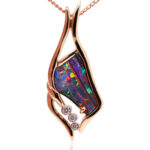

In the Middle Ages, the opal was known as the “eye stone” due to a belief that it was vital to good eyesight. Blonde women were known to wear necklaces of opal in order to protect their hair from losing its color. Some cultures thought the effect of the opal on sight could render the wearer invisible. Opals were set in the Crown jewels of France and Napoleon presented his Empress Josephine a magnificent red opal containing brilliant red flashes called “The Burning of Troy.”

The “Evil Eye”

Medieval Europeans shunned opal because of its likeness to the eyes of several “evil” animals, such as cats. Fear of the Evil Eye, common to cultures the world over, was and remains especially acute in the Mediterranean. Simply defined, the term signifies a covetous or malicious glance meant to bring harm. Witches were thought to possess this awful power in great abundance, though common people with unrealized magical talents could also wield it, albeit unconsciously. The Eye did its stuff directly and indirectly. It could strike its intended victim sick or dead on the spot, or kill family members, blight crops, sicken livestock, or summon a storm with the muscle to level a house, a village, or an entire town.

The Evil Eye’s association with the opal probably originated in Elizabethan England. There the stones were called “ophals,” a shortening of the word ophthalmos, which referred to the human eye. The Evil Eye was accepted as fact in 16th Century Britain, as was belief in omens and auguries. In the minds of superstitious Elizabethans, the occult link between ophals and ophthalmos was both obvious and ominous.

Fear of the Eye crossed the Atlantic with European settlers. In Puritan New England, colonists wore heart-shaped pendants with prayers inside to protect themselves from the godless gaze of Satan’s servants – witches, sorcerers, and magic workers who could be found in every forest clearing, every abandoned barn, and under every bed.

Ironically, they had it all wrong. The word opal had actually descended from the Roman “opalus,” an ancestor of the modern opal that was thought to heal the blind and make a person invisible to his enemies. Opalus was among the most virtuous of stones. To the Romans, who in their own way were even more superstitious than the Elizabethans, it was certainly no kin to the Evil Eye.

Plague, death & disaster

During the late 18th and 19th centuries opal fell out of favour, as it was associated with pestilence, famine and the fall of monarchies. Opal was also tied to the Black Plague, an affliction that struck in the middle of the 14th Century, ultimately eradicating more than a third of Europe’s population and much more in neighboring territories. During the decimation of Europe by the Black Death, it was rumoured that an opal worn by a patient was aflame with colour right up to the point of death, and then lost its brilliance after the wearer died. As the plague put Europe under siege, desperate people searched for a scapegoat. They found several in the persons of Jews, heretics, and, of course, the much-maligned opal.

Queen Victoria, however, did much to reverse the unfounded bad press. Queen Victoria became a lover of opal, kept a fine personal collection, and wore opals throughout her reign.

“The year 1348, an astrological Martial sub-cycle, saw Venice assailed by destructive earthquakes, tidal waves and the Plague,” wrote Isidore Kozminsky in The Magic and Science of Jewels and Stones. “The epidemic in a few months carried off two-thirds of the population of the city sparing neither rich nor poor, young nor old. It is said that at this time the opal was a favorite gem with Italian jewelers, being much used in their work. It is further said that opals worn by those stricken became suddenly brilliant and that the luster entirely departed with the death of the wearer. Story further tells that the opal then became an object of dread and was associated with the death of the victim.”

Many centuries later, a Spanish king would sully the opal’s already sordid reputation further still. In the late 19th Century, Alfonzo XII fell madly in love with a beautiful aristocrat named the Comtesse de Castiglione. The Comtesse reciprocated the King’s affection, but months before the pair were to wed the faithless Alfonzo married another woman, the Princess Mercedes. Vowing to get even, the Comtesse sent the couple a wedding present in the form of a magnificent opal set in a huge ring of the purest gold. The princess was immediately smitten by the gift and insisted that her husband slip it on her finger. He obliged, and two months later the princess mysteriously died.

After the funeral Alfonzo gave the ring to his grandmother, Queen Christina, who almost immediately thereafter also expired. After that the ring passed to Alfonzo’s sister, the Infanta Maria del Pilar. Maria died as well, apparently victim to the same weird illness that had taken the other two women. The ring was up for grabs yet again, and when Alfonzo’s sister-in-law expressed an interest, he let her have it with the usual result.

Deeply depressed by then, the King decided to end it all by slipping the ring on his own finger, just as Cleopatra had embraced the asp to terminate her own misery. In little over a month, the ring did to Alfonzo what the snake had done to the Egyptian Queen. The ring was finally attached to a gold chain and strung around the neck of a statue of the patron saint of Madrid, the Virgin of Alumdena. That put an end to the incredible chain of tragic circumstances, but was the gem really responsible for the calamities besetting this royal family? According to Kozminsky, it seems pretty unlikely.

“At this time it must be remembered that cholera was raging through Spain,” he writes in The Magic and Science of Jewels and Stones. “Over 100,000 people died of it during the summer and autumn of 1885. It attacked all classes from the palace of the king to the hut of the peasant, some accounts giving the death estimate at 50 percent of the population. It would be as obviously ridiculous to hold the opal responsible for this scourge as it was to do so in the previously noted plague at Venice. All that may be said is that in this case the opal was not a talisman of good for King Alfonzo XII of Spain and to those who received it from his hand, and that in the philosophy of sympathetic attraction and repulsion man, stones, metals and all natural objects come under the same law.”

Anne of Geierstein

The saddest opal saga is the oft-repeated misconception in the last of Sir Walter Scott’s novels, Anne of Geierstein (1829), which irrevocably linked opal to misfortune. Having not read the third volume, the public jumped to the conclusion that the heroine has been bewitched, that her magic opal discolours when touched by holy water, and that she dies as a result. On carefully examining the texts, Si Frazier, writing in Lapidary Journal, found all three accusations false. The opal, which actually belonged to Anne’s exotic grandmother, turns out to have turned pale as a warning to its owner against poisoning (which was the actual cause of her grandmother’s death). Even so, this single work plunged opal prices to half in just one year and crippled the European opal market for decades.

George F. Kunz, author of The Curious Lore of Precious Stones, says, “There can be little doubt that much of the modern superstition regarding the supposed unlucky quality of the opal owes its origin to a careless reading of Sir Walter Scott’s novel, ‘Anne of Geierstein’. The wonderful tale… contains nothing to indicate that Scott really meant to represent opal as unlucky.”

Unlucky jewellers

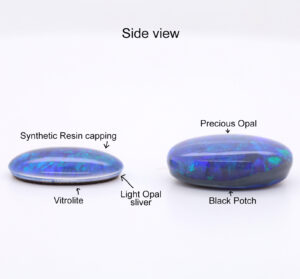

Another contributing factor to opal’s bad reputation may be the fact that opals are a relatively fragile gemstone. Opals are a soft gemstone compared to diamonds, and can be broken if mis-treated or treated roughly. This may have contributed to an overall perception of opal as “bad luck”, since anybody would be heartbroken to lose a precious beautiful opal or family heirloom.

“A possible explanation of the superstitious dread that opal used to excite some time ago may be found in the fact that lapidaries and gem-setters to whom opals were entrusted were sometimes so unfortunate as to fracture them in the process of cutting or setting,” wrote George Frederick Kunz in The Curious Lore of Precious Stones.

“This was frequently due to no fault on the part of the cutters or setters, but was owing to the natural brittleness of the opal. As such workmen are responsible to the owners for any injury to the gems, they would soon acquire a prejudice against opals, and would come to regard them as unlucky stones. Very widespread superstitions have no more foundation than this, for the original cause, sometimes quite a rational one, is soon lost sight of and popular fantasy suggests something entirely different and better calculated to appeal to the imagination.”

One royal opal did bring terrible misfortune to the hapless goldsmith who broke it during setting. The unforgiving Louis XI ordered his hands cut off! It’s no surprise that few of his colleagues thereafter had anything good to tell buyers about opal, therefore some blame opal’s maligned reputation on the difficulty that lapidaries had with cutting and setting them.

Bitter traders

Some maintain that diamond merchants of the mid 19th and early 20th centuries saw the amazing attributes of opal and realised it was going to be a serious threat to their livelihood. When high quality Australian opal appeared on the market in the 1890’s, it is understood that diamond cartels actively spread the false rumour that opal was unlucky and seriously damaged the reputation of opals.

Opal, with its stunning play of colour, was increasing in popularity and could represent a threat to the lucrative diamond trade now that it was being mined commercially. The story goes that jealous diamond traders spread the belief that opals are bad luck to protect themselves and give opals a bad reputation. Some of the rumours stuck and became the ‘old wives’ tales which are still repeated today.

The lucky stone

Isidore Kozminsky in the 1922 edition of his book The Magic and Science of Jewels and Stones states that “perhaps against no other gem has the bigotry of superstitious ignorance so prevailed as against the wonderful opal.”

He also cites several historical references to the talismanic qualities of opal including the story of a French baron who resided in London, who owned an opal that had been in the family since the twelfth century. In 1908 he took the opal to the London Pavilion where a soothsayer told him that the opal would bring him good fortune and that he was about to inherit £500,000! The London newspaper “Evening News” reported that within a few days the soothsayers’ prediction had come true, it also stated that the ancient opal had a feint inscription in old Spanish, which translated to the words “Good Luck”.

Another anecdote tells the tale of a rich city financier who took his ‘opal ring’ to a jeweller: he wanted to sell it because of the ill luck it had brought him. A tale of misfortune was recounted. As a result of wearing the ring, his wife had fallen ill, a condition that also affected his son, and he encountered among many other troubles financial difficulties and ill health. The jeweller, however, merely smiled and showed him that the stone in the ring was not an opal but a moonstone. Only his imagination had endowed the opal ring with such unpleasant properties.

There are many reports of opal bringing people luck, including the many opal miners who have made their fortunes and have lived long and prosperous lives. A well known piece of history comes from the Lightning Ridge Historical Society. Mick McCormack, a young opal miner at Lightning Ridge, rode off on his bike when war was declared and went to enlist, simply saying to his friends “I’ll be back”. A lifetime went by and a very old man was in the Lightning Ridge Hotel showing a piece of opal that he had mined and carried with him through the Great War. At the time he was showing it a buyer offered him 1500 pounds Australian for the stone. The old man said, “1500 quid? Not on your life, mate – I wouldn’t accept fifteen thousand quid. I carried this opal through the war with me and I remember one time when I thought it was my last day on earth. Men were killed all around me. Night time, it was, and there was the flashes of the guns and the shells bursting all around us. My hair was standing up and I was sweating. I was really frightened. I had the opal in my tunic pocket. I took it out and looked at it and something …sort of …calmed me down. I looked at the opal in my hand and I thought , some day, I’ve got to go back to the Ridge. And I’ll get back! And I’ll take this stone back to where it came from. No mate, money can’t buy this stone.” A couple of old miners finally realised who this old man was. They had grown up with him as kids and it was their old mate Mick who had been true to his word and had finally brought his stone home.

Some people believe that opal is bad luck… however, we at Opals Down Under believe it’s bad luck if you don’t have one! One person who would back us up is Harry Brukarz, who owned an opal shop at the corner of Martin Place and Castlereagh Street, Sydney. Harry won numerous lottery prizes in the 1940’s and 1950’s, and attributed his lottery winnings to “the luck of the opal”. The major $120,000 (60,000 pound) prize he counted among his winnings represented a tidy fortune in itself.

Despite all of this and more, the bad rap against opals has stuck through the ages. This can be partially explained by human nature. For most people, a bad opal will always have more appeal than a good one, a cursed opal more fascination than an opal that brings good luck, wards off wicked influences, or cures. We humans love a mystery, and the darker the mystery, the better we like it.

Sources :

-

“Opals”, by Fred Ward, Gem Book Publishers, 1997.

-

“Australian Precious Opal”, Andrew Cody, 1991.

-

“Fatal Attraction”, by D. Douglas Graham, Colored Stone magazine, September / October 2001.

“Thank you so much. We received our necklace today and it is just gorgeous. And appreciate you getting it to us so quickly and in time for our deadline. ” (12/02/21)

“Thank you so much. We received our necklace today and it is just gorgeous. And appreciate you getting it to us so quickly and in time for our deadline. ” (12/02/21)